Gallery 01:3

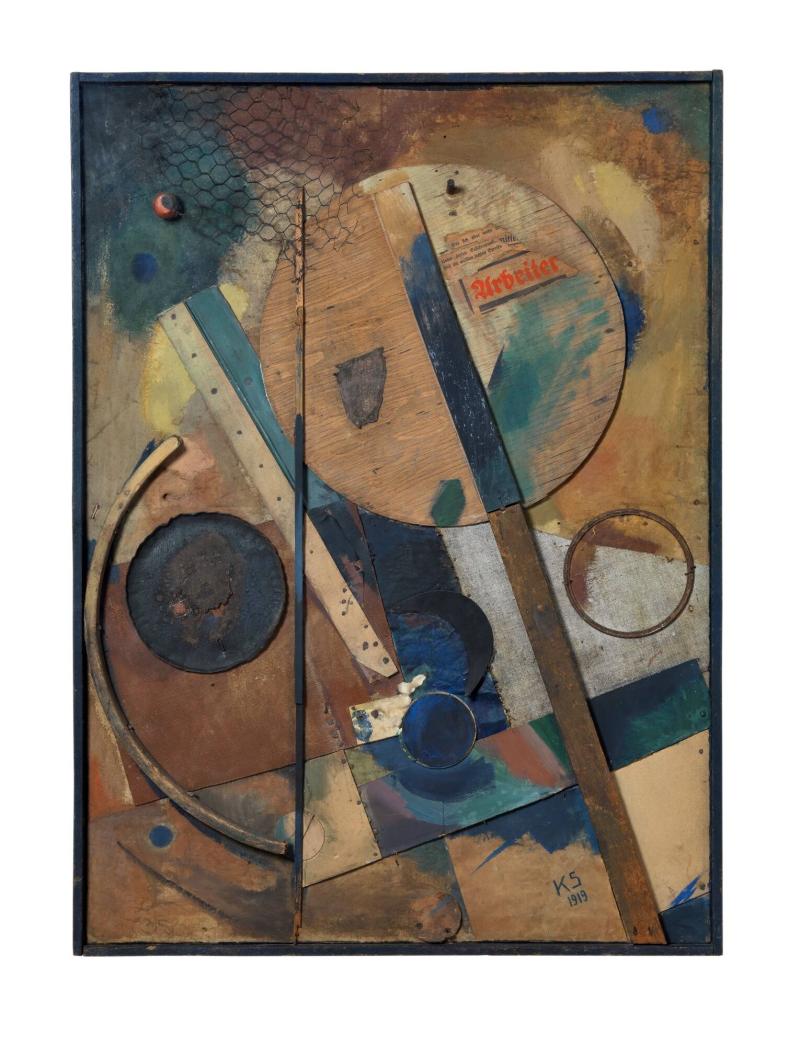

DADA AND THE CITY AS A STAGE The turn of the 20th century is a time of rapid development in Europe. Despite the colonial arms race between nations and increasing tensions between social classes, persistent peace and rising prosperity allow many to dream of a different, freer world. The outbreak of the First World War therefore marks an abrupt shift, leaving shattered hopes and unimaginable destruction in its wake. Humanity has reached absolute zero and few believe in art as a positive force in society – it is difficult to see any future at all.

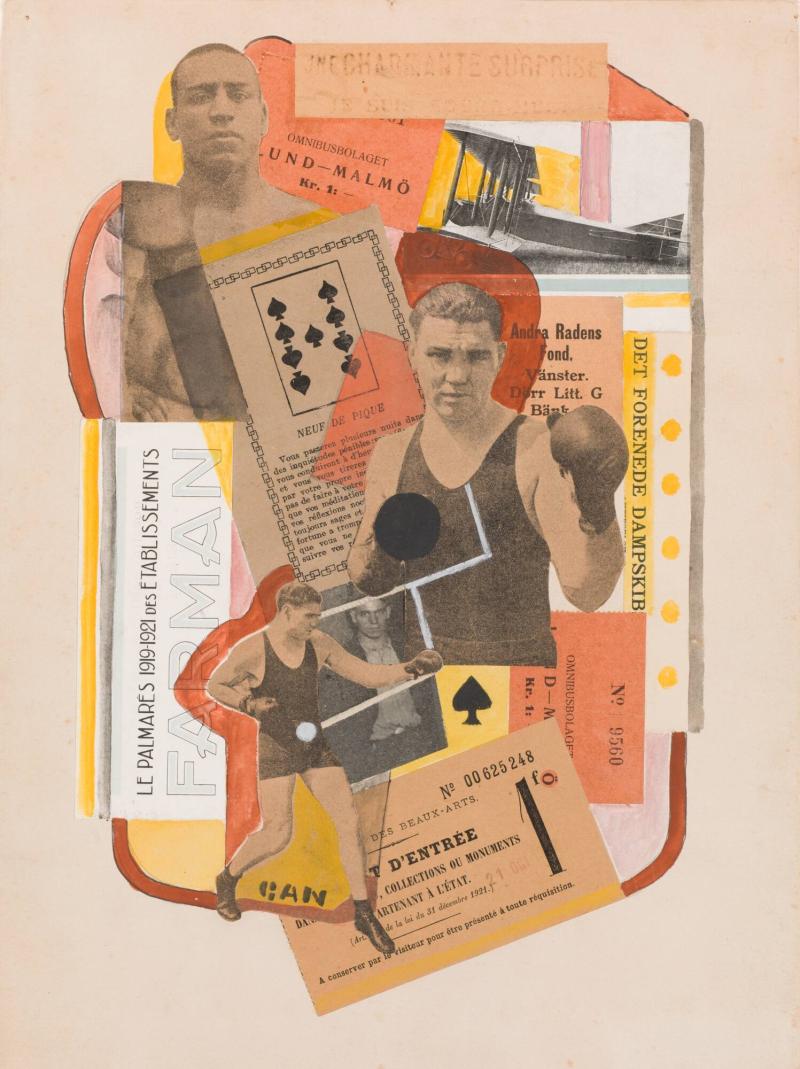

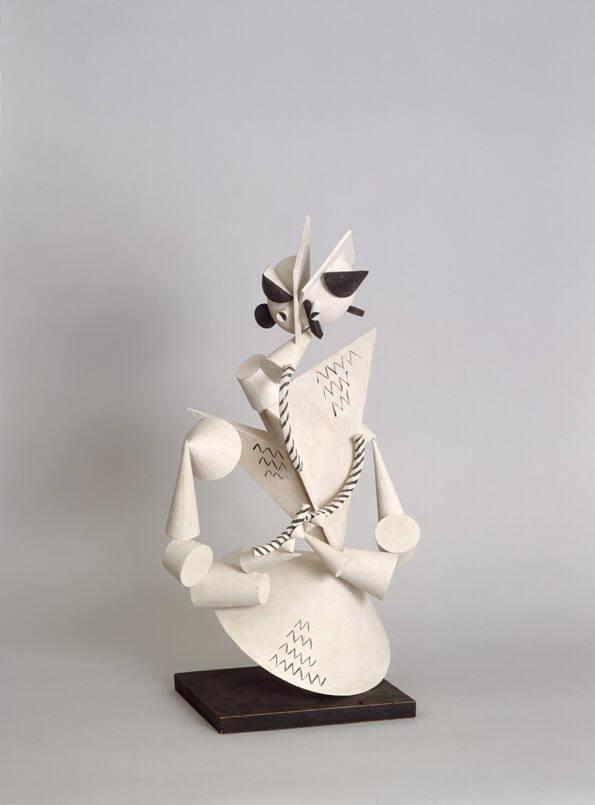

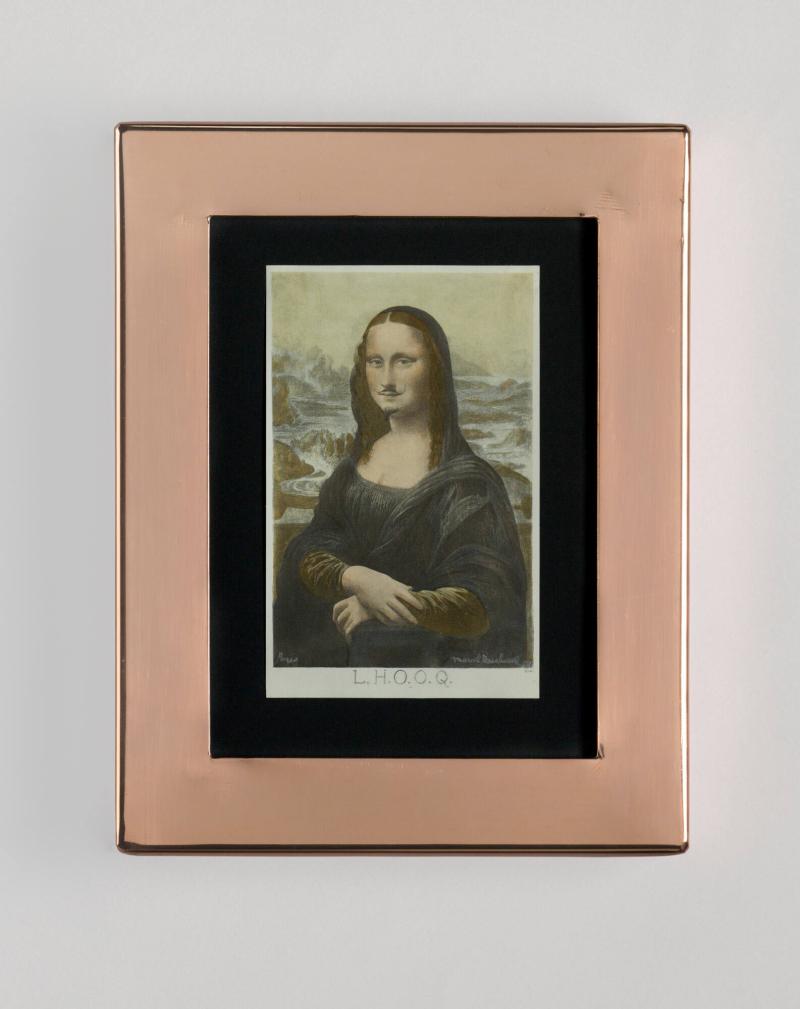

When Dada emerged in 1917 among artists and writers in Berlin, Zurich, and Paris, it was as an anti-art and anti-war movement. They shared a sense of the futility and absurdity of existence. Everything must be smashed to pieces in order to create new meaning, including art and language. Black humour becomes a valve, as do distance and irony. The irreverence of the Dada movement paves the way for Surrealism, but with crucial differences. If Dada stops at reflecting the fractured state of its time, Surrealism will rather insist on the possibility of human liberation and development through art.

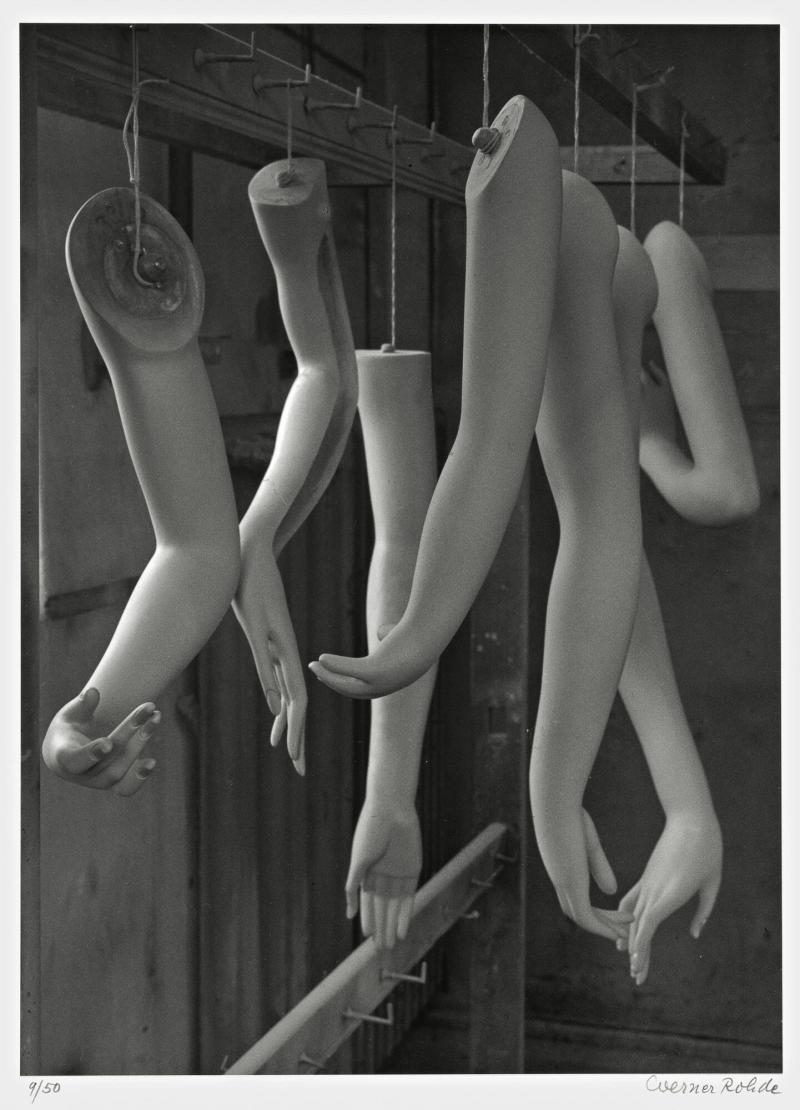

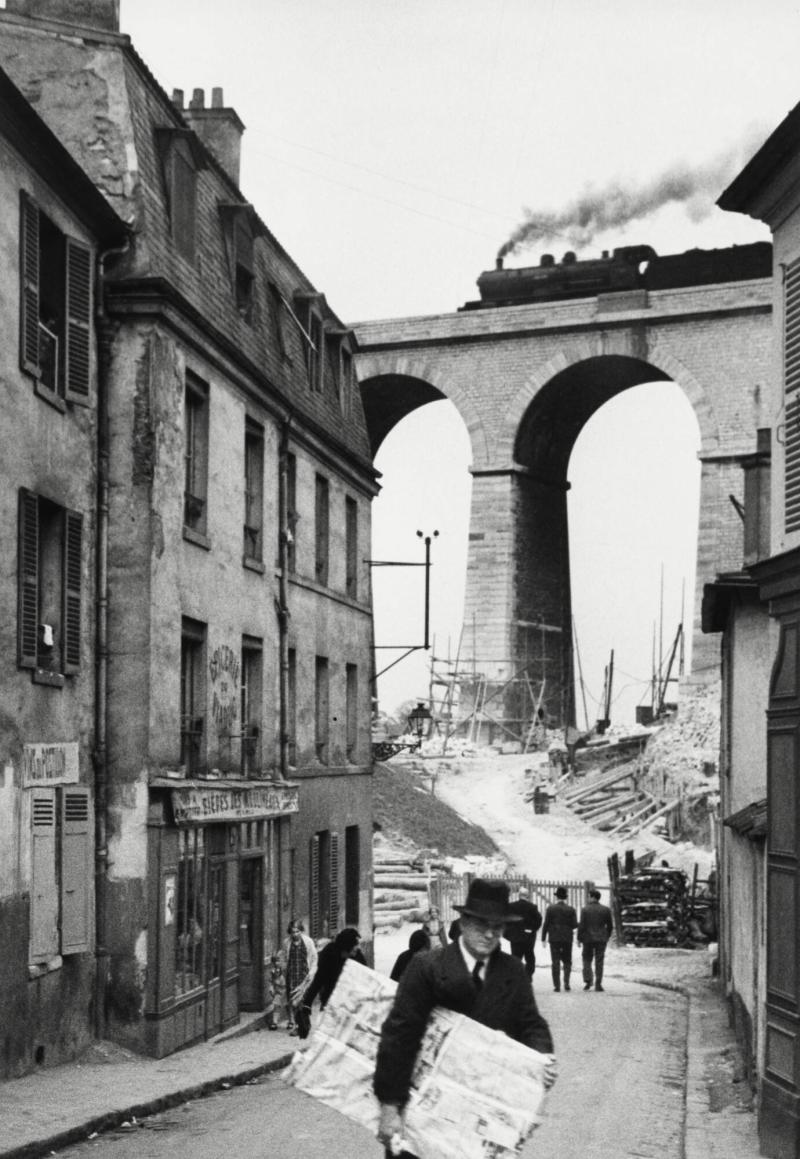

Paris experiences an economic upswing in the 1920s and becomes a dynamic center for art, dance, film, and literature. For both Dadaists and Surrealists, the modern city is both a stage and a cabinet of curiosities, a space to discover and marvel at. They see shop goods and mannequins as art objects, ready-mades. Even in the trivial everyday life, there is something astonishing and desirable to be found – but it needs to be caught out of the corner of the eye, not deliberately. The ideal pastime of the Surrealists is a dérive, to drift aimlessly and let oneself be absorbed in the moment. Wandering between the city’s cinemas, they enjoy their most important film experiences: in a series of random glimpses, without regard to the plot or genre of the films.