Gallery 01:5

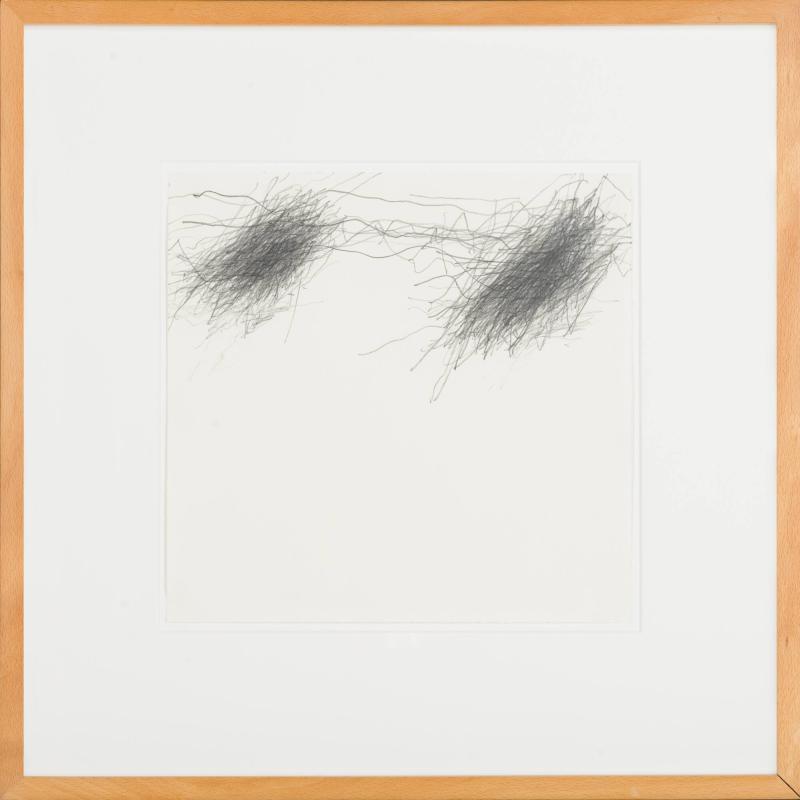

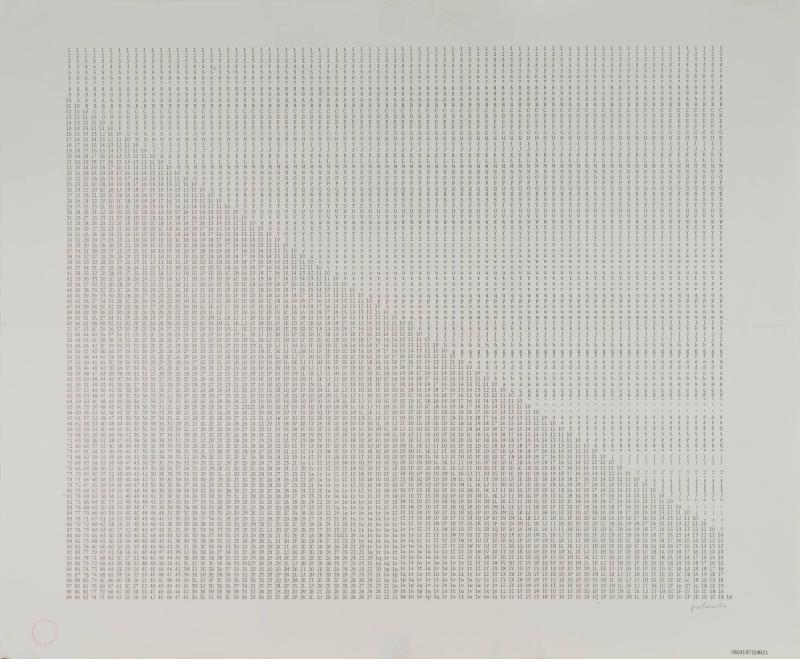

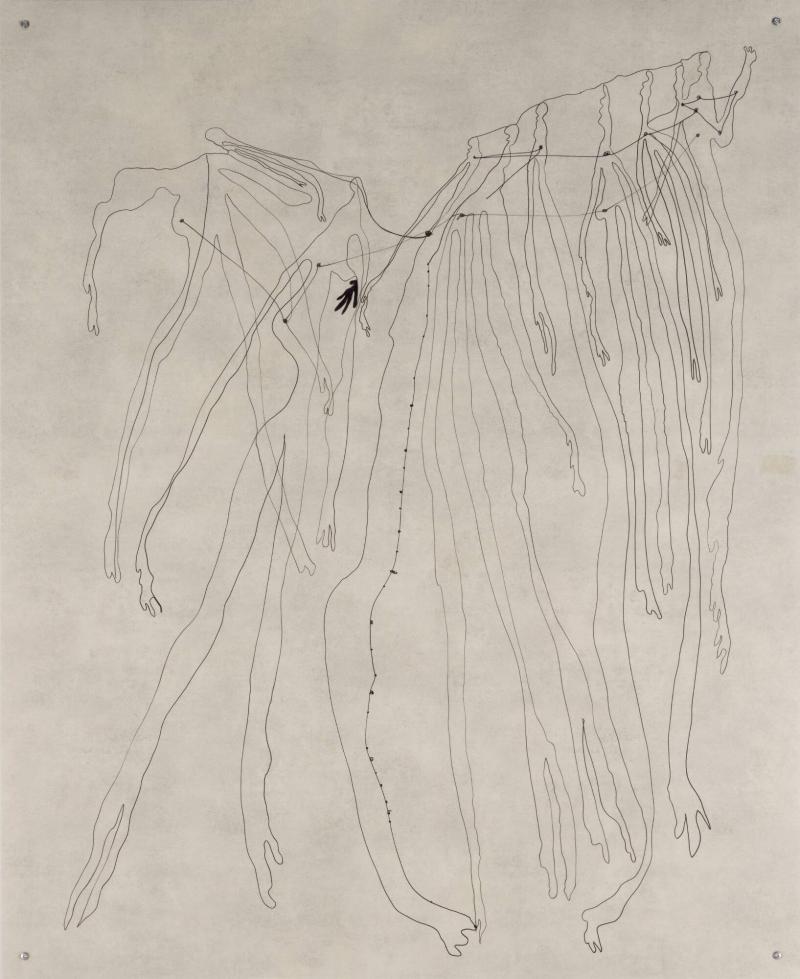

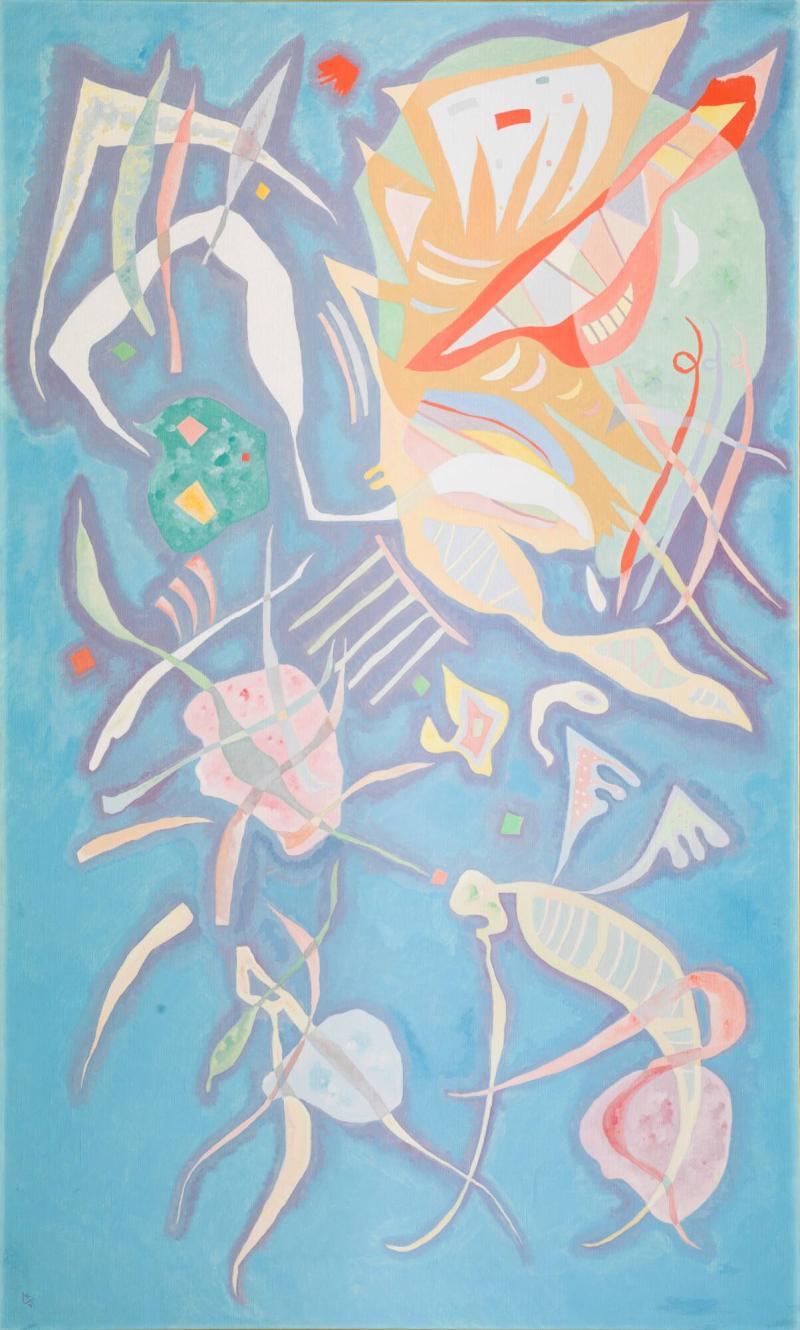

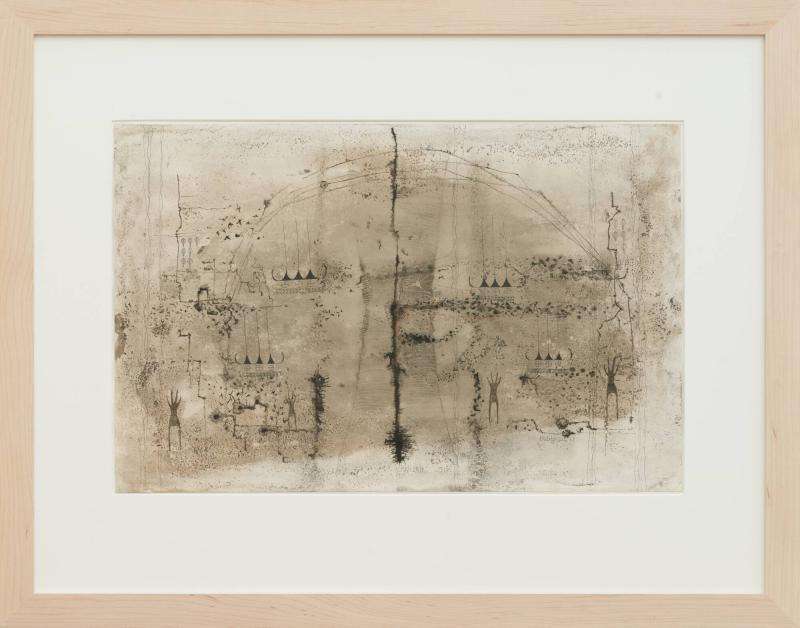

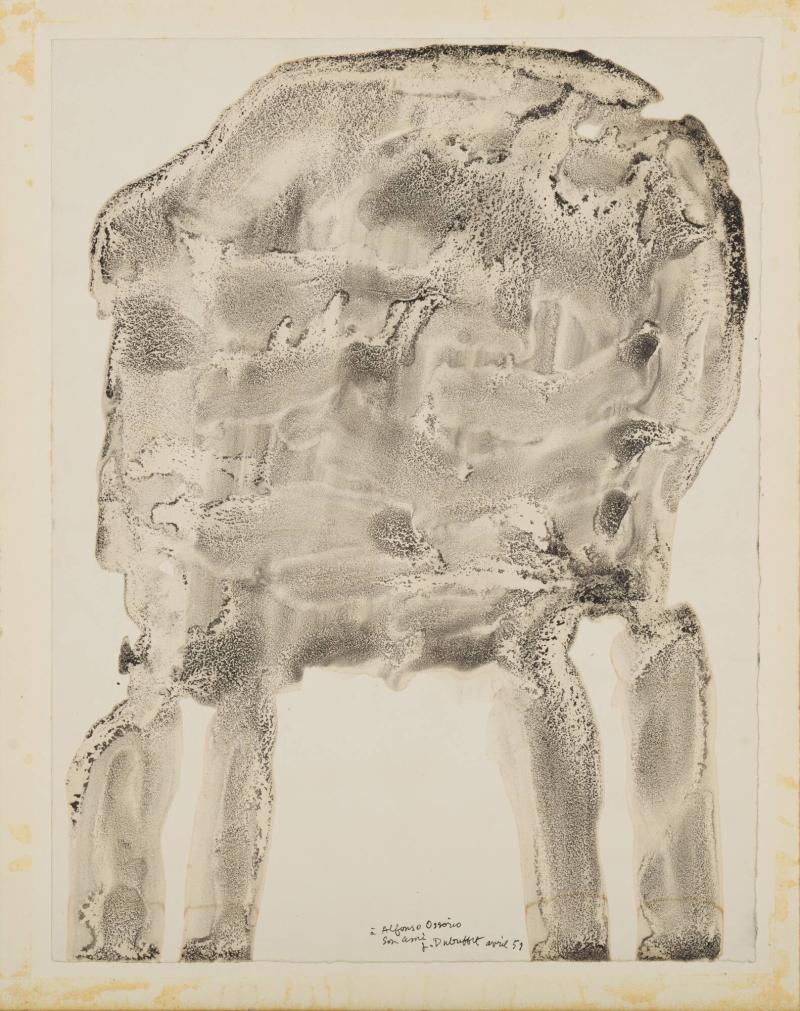

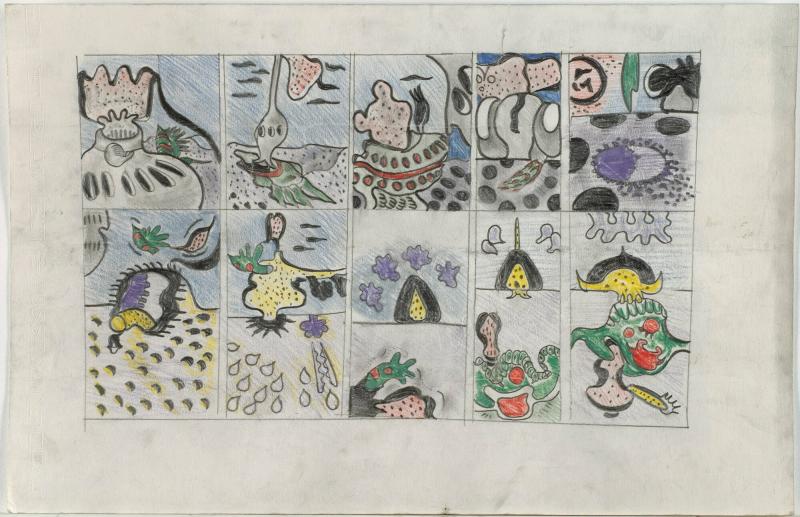

SEARCHING FOR THE INVISIBLE The artists of the interwar period regard Surrealism as a discovery just as important as electricity or magnetism, rather than as an artistic movement. The aim is to activate its redemptive power in the borderland between artistic intention and unconscious impulse. They are interested in the images produced by children and the mentally ill. As in writing, Surrealist artists work with automatism in techniques such as free drawing, collage, and frottage. For many, leaving artistic choices to chance or strict rules becomes a way of letting go of control and getting rid of their superego. Others experiment under the influence of drugs, trance states or hypnosis. There are similarities with spiritual and occult traditions of seeking an invisible inner world. Some have likened Surrealism to a non-religious form of Sufism, a strand of Islamic mysticism whose ultimate aim is to ascend into the absolute.

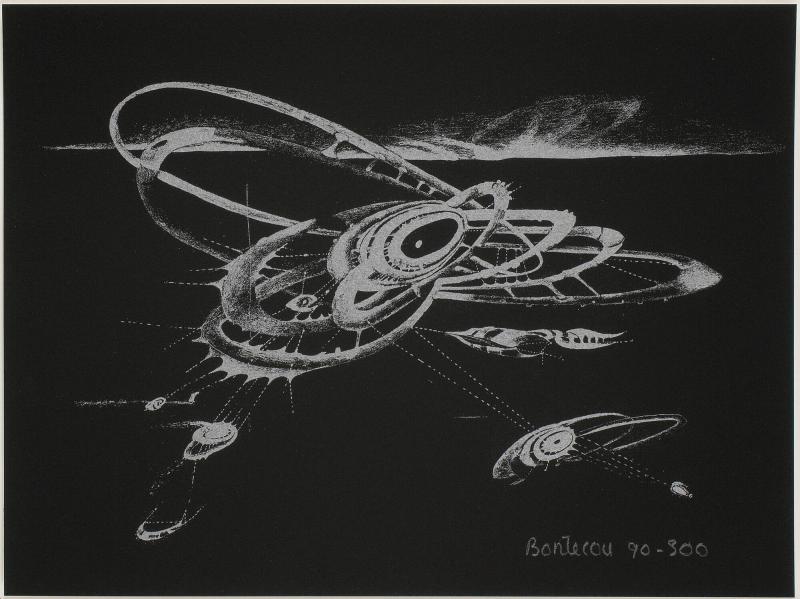

Many European artists are exiled during the Second World War, including Leonora Carrington and Kati Horna, who emigrate to Mexico. André Breton, Louise Bourgeois, and Salvador Dalí work in New York in the 1940s. Here, their ideas spread to a new generation of artists seeking subjects and expressions unencumbered by the Western tradition. Previously regarded in the United States as a decadent European movement on the margins, Surrealism’s focus on the human and the irrational is now, in the shadow of war, very much of the moment. Emerging American art movements such as Abstract Expressionism and Neo-Dada were influenced by Surrealist ideas. The happenings and anti-authoritarian social engagement of 1960s and 1970s art also have roots in the Surrealists’ vision, with influences from Eastern mysticism. In this spirit, the international Fluxus movement works with expressions that are idea-oriented, time-based and beyond language.